Day 4 of the 2020 trip to Eastern Washington

/Carol Hasenberg, Past President of GSOC and current Field Trip Director, visited eastern Washington recently with her husband John. They based the trip primarily upon the geologic topics covered in the “Nick From Home” video series by CWU professor Nick Zentner. If you’ve come in through the back door, i.e., Facebook or some other link directly to this page, you may want to start at the introduction page to the trip.

Overview of Day 4.

Our first stop in the Grand Coulee was near the south end of Lake Lenore.

Today in Othello the forecast is for even hotter weather, about 105 F. We thought that traveling north to Alta Lake would be a bit cooler. Turned out that 99 doesn’t feel much different!

Anyhoo, we broke camp at Potholes and began a journey to and through the Grand Coulee of Washington. This would be our last journey through “The German Chocolate Cake” as Zenter calls the Columbia River Basin, filled with layer after layer of dark Columbia River Basalt. I was looking with some anticipation on viewing some metamorphic rocks.

But let’s not get ahead of our story. We started the drive similarly to the previous day’s trip, passing through Moses Lake and skirting around Ephrata on the Hwy 17 bypass (I know, the map does not show this correctly) and I think we made a stop for ice at the town of Soap Lake. Soap Lake (the lake) is an interesting feature because of its history as a health spa in past years. Soap Lake is full of concentrated salts and minerals from its role as a remnant lake of the Ice Age and has a pH reading of 9. Amara & Neff said that the Columbia Basin Project irrigation system was built to bypass Soap Lake for this reason.

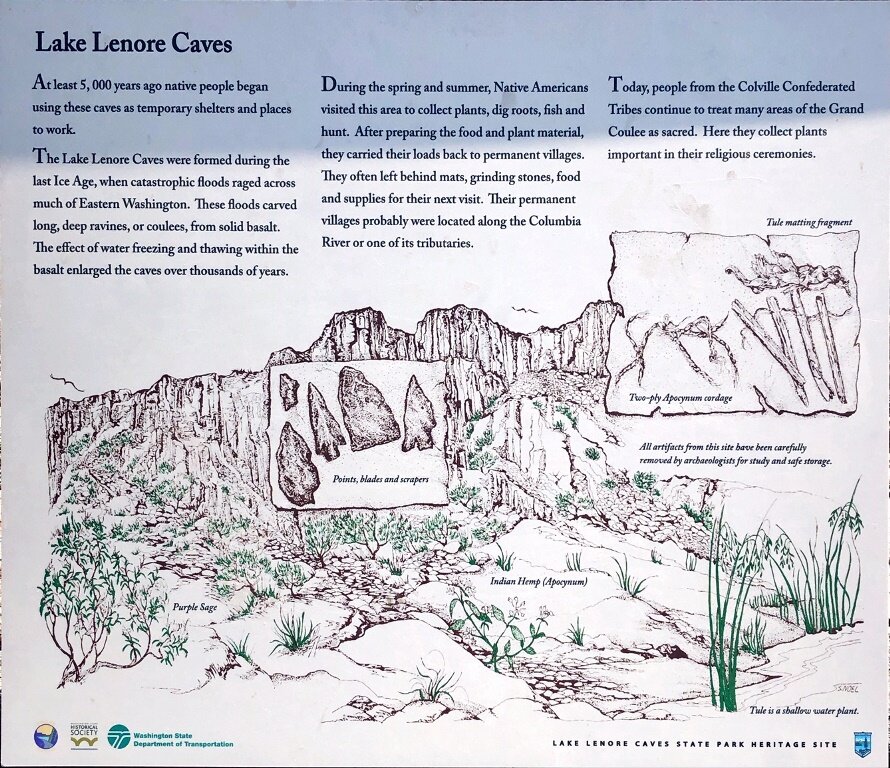

I had switched reference books for this part of the trip to Amara & Neff because they had a lot of information about the Grand Coulee. We followed their tour right up through the coulee. Their tour turned me onto the Lake Lenore Caves, where we stopped for a short hike up the side of the coulee to caves that had been used by the local tribes as temporary lodgings while they fished, hunted, and collected plants in the area. Caches of materials dated at thousands of years old have been found in the caves.

The remnants of the cross section of the Grand Coulee in Lake Lenore shows the outline of the monocline, which was the weakness exploited by the Ice Age Floods to develop a coulee along the breadth of the feature.

Driving up the west wall of the Grand Coulee towards Dry Falls, one can see further evidence of the monocline.

As we traveled from Lake Lenore to Dry Falls, we could see the remnants of layers sloping down towards the east side of the coulee. This slope is called the Grand Coulee Monocline. The Ice Age Floods were able to rip apart this area more easily than the flat intact basalt layers.

Dry Falls from the overlook. It’s no wonder that J Harlen Bretz could see that massive amounts of water had come through here.

No wonder also that at Dry Falls you will find the commemorative plaque honoring the work and insight of J Harlen Bretz. Click on the pic to enlarge and read the plaque.

Dry Falls is an incredible sight. It cannot be viewed without a sense of awe regarding the forces that created it. Nick Zentner devoted an episode, Nick From Home Livestream #17, to J Harlen Bretz, the man who challenged the geologic community to view the features created by the Ice Age Floods and to see them for what they are.

Well, onward and upward. The floor of the Grand Coulee takes a step upward at Dry Falls, and the coulee walls ramp up accordingly as you head north. This part of the coulee is mostly filled with Banks Lake, the biggest storage chamber for the water of the Columbia Basin Project. It is so elegant how the men designing this project took advantage of this wonderful, empty corridor to create the biggest irrigation project in the United States.

Steamboat Rock, a flood survivor, sits in the middle of Banks Lake.

Lovely Cretaceous granodiorite makes a nice contrast with “The German Chocolate Cake.”

As we drew level with Steamboat Rock, I began to look near the road for an outcrop of pale Cretaceous granodiorite. This was mentioned in both Amara & Neff and Miller & Cowan references. As much as I like to see a nice wall of basalt, I’d seen quite a few of them in the last 4 days, and was ready for something new. I wanted to turn back the clock into deep time.

Eventually Banks Lake came to an end and we kept an eye out for our turn west on Hwy 174. We were going to cut across the northern extremity of the Columbia Basin, which is a high plateau in this area, to Bridgeport, where there is a bridge over the Columbia River. As we headed up Hwy 174 from the Grand Coulee, we crossed over the feeder canal for Banks Lake. The head of the coulee is much higher than the Columbia valley, and even with the water height increase from the Grand Coulee Dam at Roosevelt Lake, the water still must be pumped up 280 feet to a canal that feeds Banks Lake.

Further up the hill was a viewpoint atop hills of Eocene granite down to a stunning view of the Grand Coulee Dam.

Grand Coulee Dam from the viewpoint.

Glacial moraine along Hwy 174 to Bridgeport.

Passing over the plateau to Bridgeport, we saw a lot of glacial moraine material. And, although I did not get a picture of this, there were lake deposits from the Ice Age, possibly Glacial Lake Columbia. I’ve located a blog that talks about this by Dan McShane, an engineering geologist with Stratum Group based in Bellingham, Washington.

After we crossed the Columbia at Bridgeport, we began to see large terraces along the Columbia River. The terraces line the north side of the river all the way to Pateros and Alta Lake, where we were to camp for the night. The hills behind the terraces are metamorphic rocks of the Crystalline Core Complex of Washington.

Miller & Cowan describe these high terraces as glacial outwash terraces from the Okanogan Lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Further down the Columbia River south of the glacially covered zones, there are flood gravel deposits. Also, the Columbia River has cut down into its bed and left some regular alluvial deposits stranded at higher elevations along the river. You can see how this might get a bit confusing. So I’m sticking to the Miller & Cowan definitions for this location.

Finally Alta Lake was in sight! But it was only about 3:00 in the afternoon and nearly one hundred degrees. We hung out in the picnic area again, where sprinklers were making the rounds, and Lucy and I took little runs through the sprinklers from time to time. Our campsite was in a beautiful Ponderosa Pine forest and I was looking forward to checking out the metamorphic rocks of the Alta Lake complex…in the morning! So we turned in at last and slept the night.

Click here for Day 5.