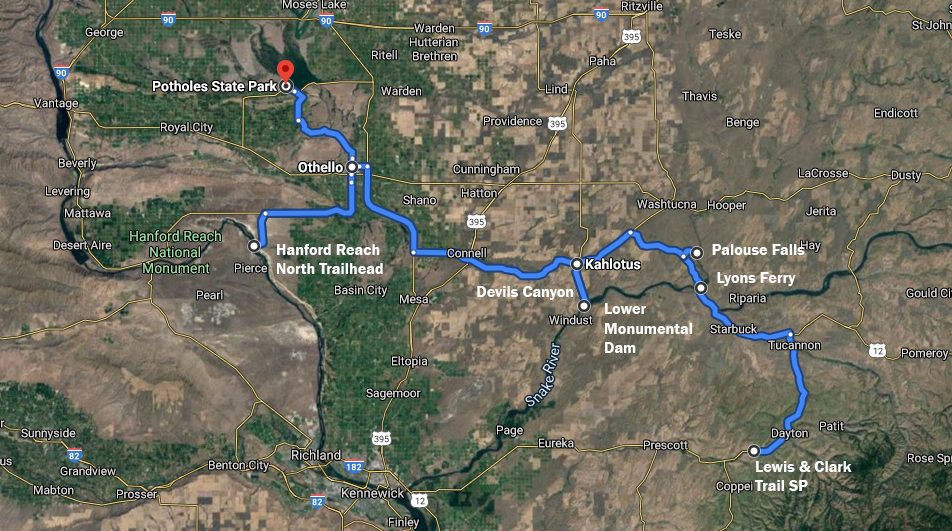

Day 7 of the 2020 trip to Eastern Washington

/Carol Hasenberg, Past President of GSOC and current Field Trip Director, visited eastern Washington recently with her husband John. They based the trip primarily upon the geologic topics covered in the “Nick From Home” video series by CWU professor Nick Zentner. If you’ve come in through the back door, i.e., Facebook or some other link directly to this page, you may want to start at the introduction page to the trip.

Overview of Day 7.

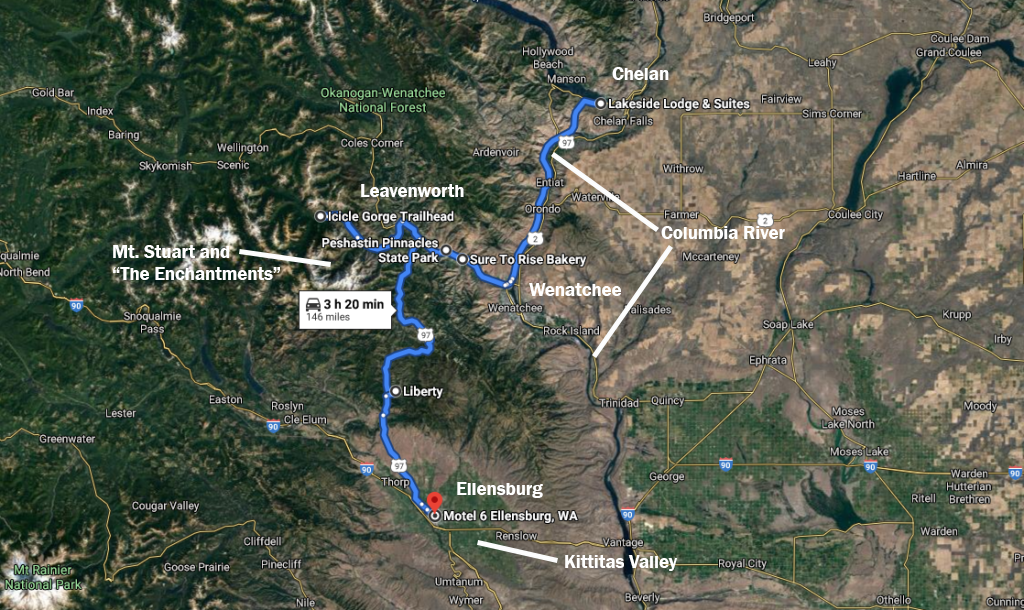

I need to do a bit of a catch-up from Day 6 as I ran out of steam by the time we got to Ellensburg in the Day 6 article. But we toured Ellensburg in both the evening of Day 6 and briefly in the morning of Day 7, so it’s good to combine the experiences. We were obviously tired of geotouring by the time we hit the Kittitas Valley, so we zoomed in on I-90. We noticed two things right away — the temperature was 90 F, although it was much hotter in Wenatchee, and the Kittitas Valley can be a wind tunnel. This worked in our favor today.

Map of Ellensburg. Click to enlarge.

We drove around looking for a motel, and most of these were situated in the south near I-90, but we wanted to avoid the freeway noise and be closer to the university, so we ended up at Motel 6. It was about 1/3 the cost of the previous night’s lodging, and included a mini kitchen. The room was very clean. The parking lot was about the size of a football field and mostly empty, so I think they were hurting from the COVID-19 closures. They probably get a lot of business from Central Washington University, including the football crowd.

Next we toured the university district, and had a fun dinner at the retro Campus U-Tote-Em hamburger emporium. We drove around town a bit more, noting that, except for the university, the town of Ellensburg is a very ordinary, small town USA kind of place. It is the setting which makes it such an outstanding place for geologists. We wound up at a very nice play field park, Rotary Park, and took Lucy on a walk around one of the stadiums. The wind was very strong here so we were careful about walking from one sheltered spot to the next.

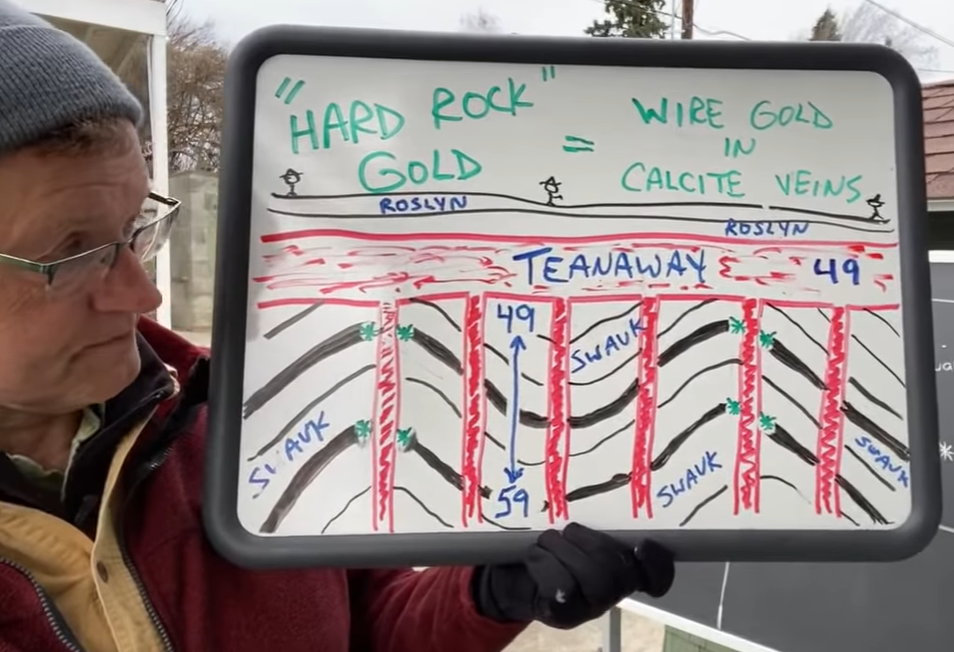

The next morning we woke up with the realization that we would be home today! After picking up a pecan roll at Vinman’s, we hit the highway early and headed south on Hwy 821 so as to go through the Yakima River Canyon. Yakima River Canyon is Zentner’s prime example of the river predating the hills that surround it. The Yakima River used to lazily meander over the top of the pancake-flat layers of Columbia River basalt and pre-basalt sediments, and then, about 16 million years ago, things started to change. Tectonically what was happening was that California was pushing the southwest corner of Oregon northward, and Oregon was rotating clockwise in response, and with the bulwark of the British Columbian Coast Plutonic Complex to the north resisting any northward motion, the state of Washington gets squeezed. This produced the Yakima Fold and Thrust Belt whose age ranges from 16 to 10 Ma.

This left the Yakima River no alternative but to drill down into the layers of Saddle Mountain, Wanapum, and Grand Ronde Basalt flows, and the original meandering path of the river was preserved. There are also some outcrops of the Ellensburg Formation, which was deposited inter-fingered between the upper Grand Ronde flows and between the Grand Ronde and the Wanapum members of the Columbia River Basalt. It consists of lakebed, riverbed, and volcanic sediments, from lahar flows to tuffs, and records eruptions of the Cascade Range about 15 Ma.

Map of the Yakima River Canyon showing its meandering character.

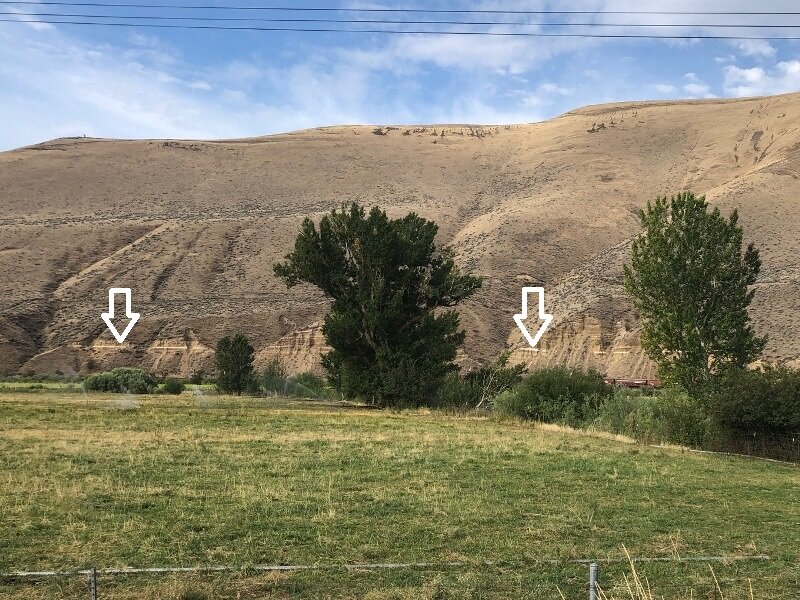

The other chief characteristic of the Yakima River Canyon is the landslides, mostly in the form of shallow debris flows and translational landslides. Some well-shaped bowl-like areas have been sculpted by this process throughout the canyon. At one point there is a prominent white stripe on the far side of the canyon, and this is suspected to have been a layer of Mazama ash (7.7 ka), but not so far confirmed, according to Miller & Cowan.

Of course I must also recommend a couple of livestreams as reference — Nick From Home Livestream #4 - Ancient Rivers and Nick From Home Livestream #23 - Yakima River Canyon and also Nick on the Fly #3 - Yakima River Canyon. In addition, there is an IAFI Ellensburg field trip guide of the Ellensburg Area available on the web. I also found additional info about the Ellensburg formation from Dan McShane’s blog, and also a Yakima Valley wine website. (Scott Burns, this one’s for you!)

After leaving the Yakima River Canyon, we traveled down the slope of the Yakima Ridge into Yakima. On the Day 7 overview map above, I’ve marked all the wrinkles in the Yakima Fold and Thrust Belt that we transected in driving down to the Columbia, via Hwy 821, I-82, and US 97. Yakima County was a veritable hotbed for COVID-19 at that point, so we didn’t stop anywhere until we crossed the Horse Heaven Hills and ate lunch at Brooks Memorial State Park.

We had decided to take the Washington side of the Columbia Gorge west until at least reaching Hood River, because we’d never been that far east on Hwy 14. It proved to be well worthwhile — we were out of the nutty freeway traffic, and traveling at good speed high above the Columbia River. First stop was right where US 97 intersects Hwy 14 — the Stonehenge Memorial to the local men who lost their lives in WWI. Every time I have looked upon this monument I think it perfectly compliments its dramatic surroundings.

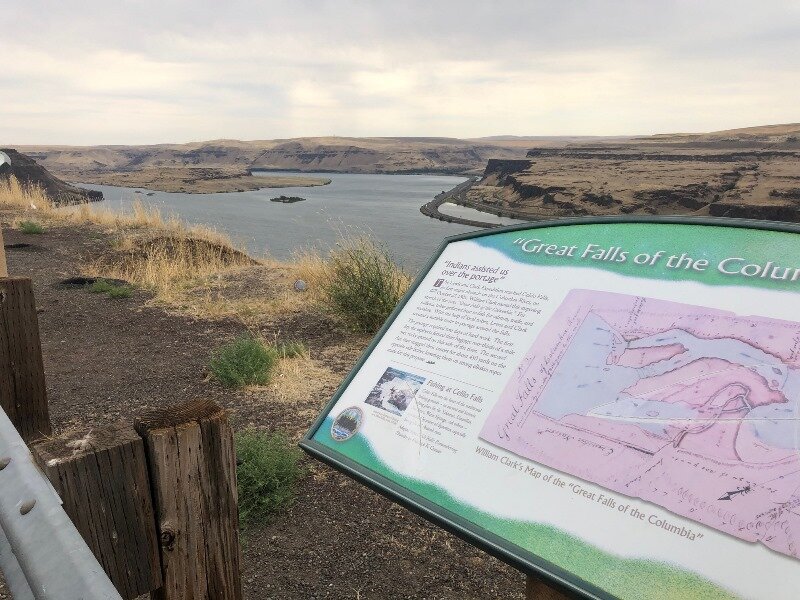

We also paused at an overlook above Wishram Heights across the river from Celilo. We’d have been looking down into Celilo Falls here, had the Dalles Dam not been built. Driving along at this height above the river, and at nearly the top of the level of the floods, it was so much easier to see the scale and imagine the floodwaters filling the gorge.

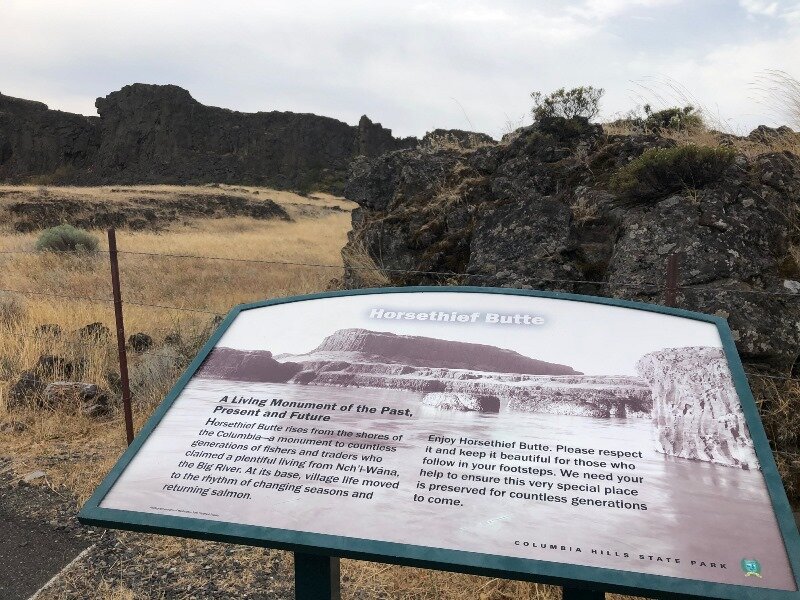

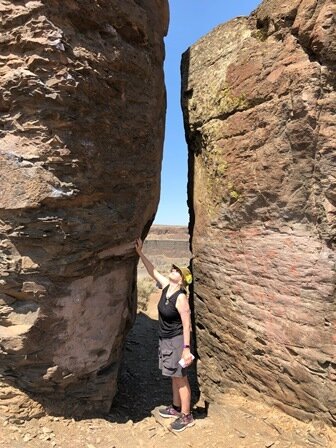

Our last stop was at Horsethief Butte in the Columbia Hills, just east of The Dalles and across the river. Here floodwaters skirted through a plateau, creating a channel through the hills and sculpting some nice basalt features, including Horsethief Butte.

And so we returned home, tired but with great memories of all the amazing landscapes we’d seen. All that was left but the write-up. This article serves as both a chronicle of the journey and a field trip guide for those of you who might want to venture forth into the wilds of Washington State. GSOC has not ventured far into Washington since our trip to Wenatchee in 2002. I think it’s high time we did. We fervently hope we will be able to do a full field trip season next year.

I’d also like to dedicate this whole adventure to Nick Zentner, who inspired and entertained us during the long home-bound days this spring at the outbreak of COVID-19. It helped to keep us sane and engaged with the world.

There are also a lot of more blog pages we could add to this article. Perhaps some of you have traveled or would like to travel to see some great geology. If you like, send some pictures with captions to my field trip director email address, fieldtrips@gsoc.org, and we will get them up on the website!

Carol Hasenberg

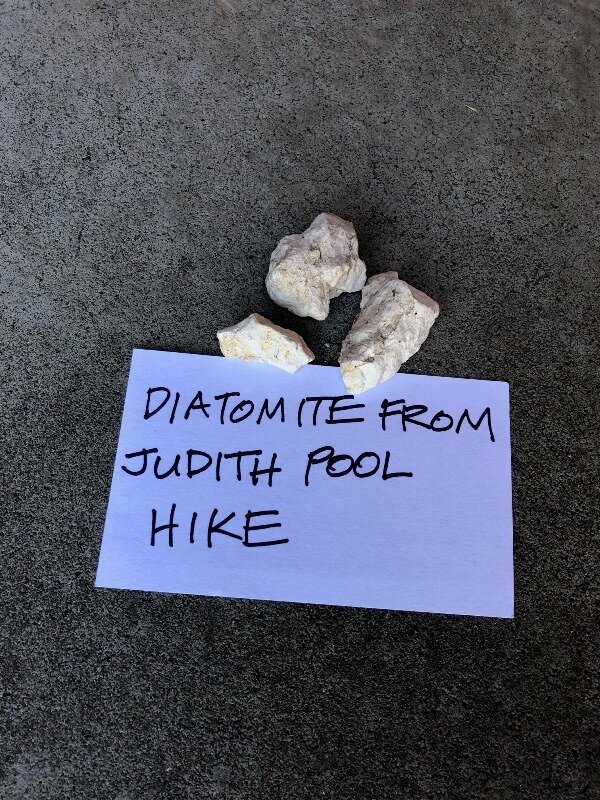

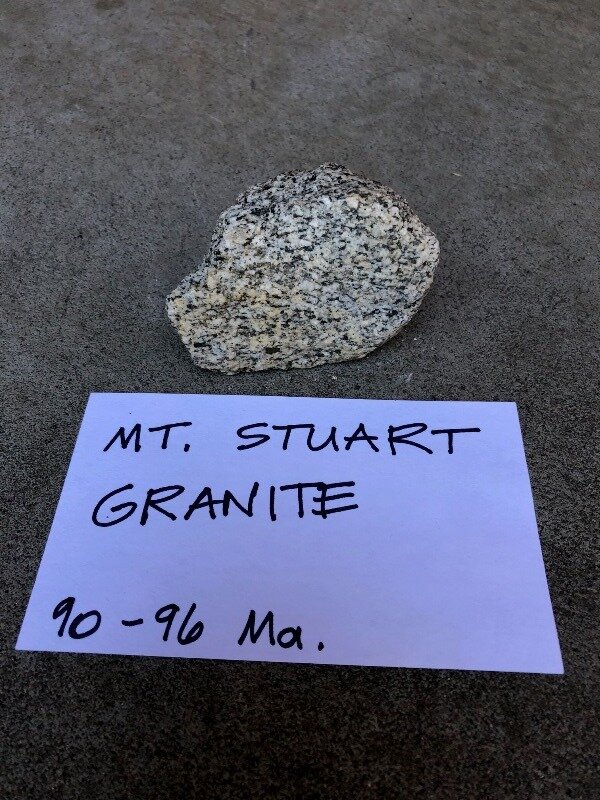

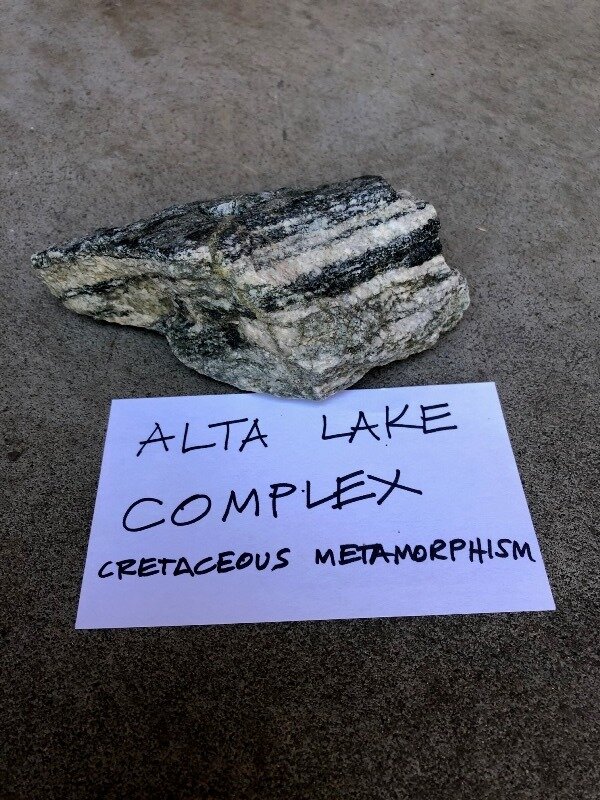

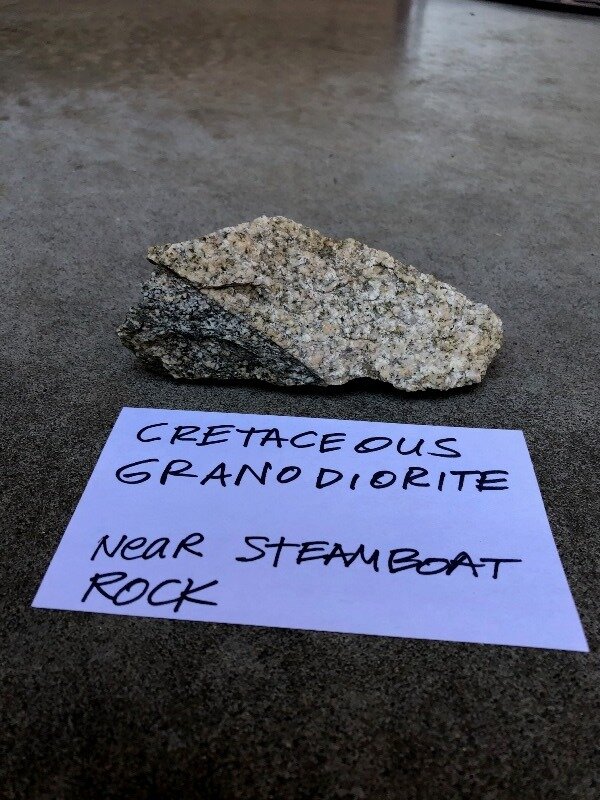

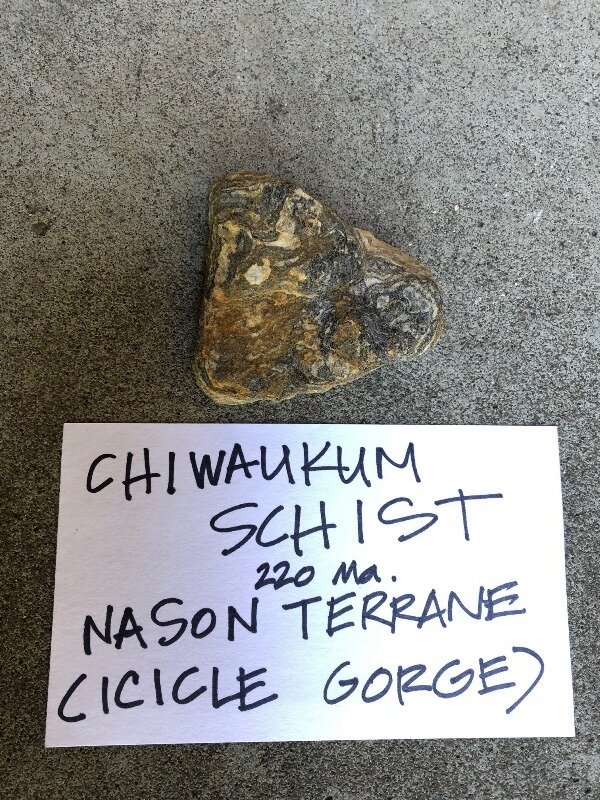

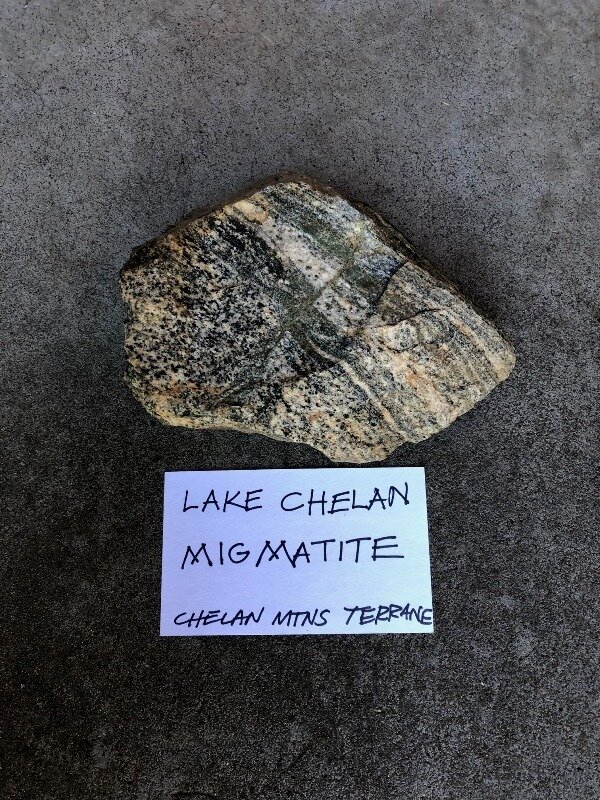

Postscript: My rock collection from the trip: