Kilauea’s 2018 Eruption

/by Carol Hasenberg

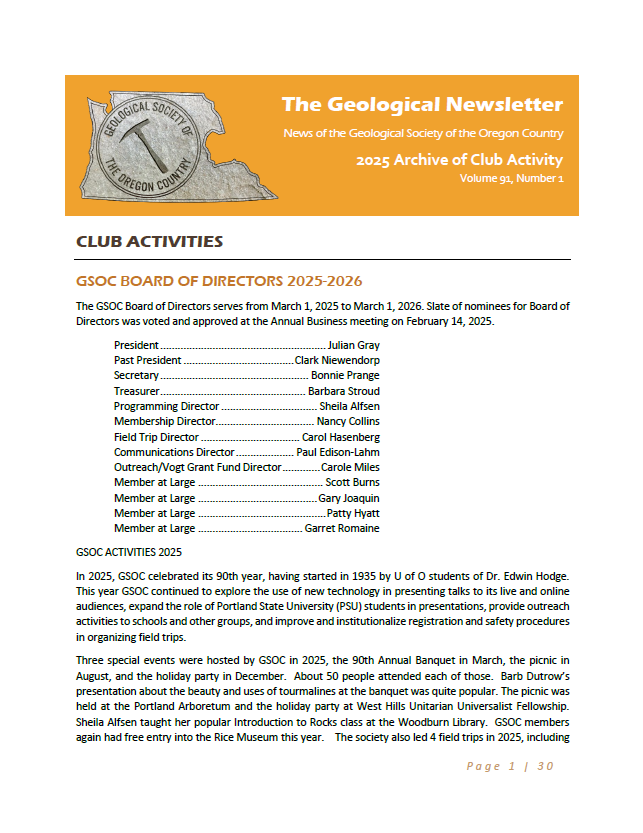

Scale of three of the volcanoes on the Big Island: Massive Mauna Loa in the center has erupted 33 times in historical times. It dwarfs the more active Kilauea. Hualalai shown in the distance is an active volcano and poses considerable risk to the Kona coast. Photo by USGS.

This article has been written to ‘peak’ your interest in the 2018 Kilauea eruption on the ‘Big Island’ of Hawaii in the Hawaiian Islands. USGS researchers have recently released a summary of the events of 2018 and their importance to the study of shield volcano eruptions in an article in Science on January 25, 2019, entitled ‘The 2018 Rift Eruption and Summit Collapse of Kīlauea Volcano.’

The public can access the Science article through the USGS HVO website, free of charge. Just follow the link under HVO News.

Perhaps ‘peak’ is not the right word when referring to Kilauea. Travelling up Hwy 11 around the South Point area to the Kilauea caldera, you cannot even see the summits of Mauna Loa on the left and much smaller Kilauea on the right. These young Hawaiian shield volcanoes are massive and wide. Between Na’alehu and Pahala there are some weird looking slump blocks on the slope of Mauna Loa to the left. And as you approach the summit of Kilauea, there is a small canyon formed in the crease between the two volcanoes on the left. But once you see the Kilauea caldera you won’t mistake this for anything less than an active volcano.

A recent photo by the author from near the south side of the Halemaumau caldera on the peak of the Kilauea volcano. This is as close of an approach to the caldera as the USGS will allow these days. Before the eruptions in 2008, you used to be able to drive around the caldera, park your car and walk right up to the edge and look in. That parking lot and viewpoint have fallen into the current caldera. Most of the caldera rim drive has also been closed, and pedestrians may walk down a section to this viewpoint.

Not that it’s so easy to get a view of the caldera these days. It’s about twice the area as it was last year and five times deeper. Access is restricted to the Jaggar Museum and HVO Observatory, which is now perched much closer to the edge. But if you visit the volcano, you can get a view from the Steaming Bluff near the entrance to the park, and if you’re willing to walk about a mile on a paved road, you can get a better view from the southeast side near the junction of Crater Rim Drive and Chain of Craters Road.

But let’s get back to the Science article. It covers the buildup to the 2018 eruption, the M6.9 earthquake caused from volcano flank slippage, the transport of magma from the summit caldera and Pu’u O’o cone to the Lower East Rift Zone (LERZ), the LERZ eruptions, the summit collapse, the use of emerging technologies in documenting the various aspects of the eruption, and lessons learned by the geologic community from the eruption.

Above – orientation to the Big Island: Hawai’I is a pretty big place – the island contains 5 volcanoes, and cities are located away from most active volcanism and in the most level spots. Volcanic features are shown in yellow and orange, and cities and towns are in blue. The massive bulks of Mauna Loa, Mauna Kea, and Hualalai dominate the scenery. The slopes of Kilauea are fairly shallow in angle, and unfortunately, this attracts development. Map base is from Google Maps, which has not yet been updated since the 2018 eruptions.

I have been most interested in two aspects of the eruptions, the evacuation of lava from and the collapse of the Halemaumau and Pu’u O’o vents, and the M6.9 earthquake and slippage of the flank seaward from the LERZ. I remember watching the webcam infrared images taken from the lip of Halemaumau and watching the lava drain out the volcanic plumbing as the eruption was imminent. Later as the summit collapse was in progress USGS did several drone flybys of the caldera and those were fascinating to watch. Likewise the lava drained from the Pu’u O’o vent, which had erupted continuously for 35 years, leaving another sizable hole in the landscape (about 1000 feet deep). The Science article covers the collapse of the summit (Halemaumau) caldera, but it does not have images of similar changes of Pu’u O’o, which were available during the eruption.

The slippage of the flank of Kilauea touches on a topic I find fascinating and I will cover this in the next article, that of destructive phase processes and the Hawaiian submarine landslides. For this discussion let’s look at what’s happening with the pull of gravity on Kilauea. All Hawaiian volcanoes have zones of weakness and cracking, called ‘rift zones’ that radiate out from the center caldera. Freestanding volcanoes tend to develop three rift zones, but since Kilauea is buttressed on one side by the bulk of Mauna Loa, it only has two of these zones. The East Rift Zone is the one that has been active in recent times, and the 2018 eruption was in the eastmost portion of this rift zone.

In this USGS map, the 2018 lava is shown in salmon orange. Older flows are in lavendar. Theis map is part of the USGS HVO website under the 2018 Activity tab.

Hawaiian volcanoes are built upon a bed of, well, rubble. This rubble consists of pillow basalts weakened by exposure to seawater and glassy sand from the submarine building phase of the young volcano. Once the pile of volcanic layers grows to a significant height, then mass-wasting, gravity-driven processes begin to happen. Massive slump blocks begin their inexorable slide seaward and more rapid debris avalanches also occur. This volcanic spreading is abetted by the pressure of the magma in the vent plumbing and dikes of the rift zones. In effect marine volcanoes pry themselves apart.

Right before lava started to erupt from the Lower East Rift Zone (LERZ) in 2018, there was a large earthquake (M6.9) from a slip of up to 5 meters seaward in the block of material to the south of the LERZ. HVO geologists suspect that this event opened up a gap in the rift zone and allowed magma to head downrift, which had not happened since 1960. The Science article has a well developed discussion of the earthquake and flow of magma down the rift zone.

All very exciting reading for us geology buffs. In our recent holiday in Hawaii, my group visited the top of Kilauea, which is in the Hawaii Volcanoes NP; however, we did not go down to visit the areas that were inundated by the lava. These areas are privately owned, and also the recent lava flows were a disaster for the local community. It is very unfortunate that in its normal eruptive cycle, Kilauea was also responsible for destroying the homes of many residents in the area. Perhaps the political lessons learned will be helpful in preventing this cycle from repeating itself.

References and Additional Reading

Oregon State’s reference page on “Hawaiian volcanism” is a very detailed article on the subject. It contains a discussion about the giant landslides near the end.

“Evolution of Hawaiian Volcanoes” page from the USGS HVO website has a basic discussion about volcanic evolutionary stages and destructive processes.

John S. Schlee, Herman A. Karl, and M.E. Torresan, “Imaging the Sea Floor,” U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2079, *U.S. G.P.0., 1995. Describes using the GLORIA side-scanning sonar to map US territorial waters from 1986-1991. The Hawaiian landslide images used in this article comes from this publication, and this sonar mapping work revealed the presence of these massive underwater landslides to the geologic community. Modern sonar techniques employ both side-scan and multibeam techniques.

Moore, J. G., Normark, W. R., & Holcomb, R. T., “Giant Hawaiian Landslides,” Annual Review Of Earth And Planetary Sciences, Volume 22, pp. 119-144, 1994. This article summarized discovery and knowledge of giant Hawaiian landslides in the mid 1990’s, and is referenced quite frequently.

Julia K. Morgan, Gregory F. Moore, David A. Clague, “Slope failure and volcanic spreading along the submarine south flank of Kilauea volcano, Hawaii,” Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, September 5, 2003. This article discusses the particulars of the ongoing volcanic spreading in the south flank of Kilauea. It is quite technical, but from summary remarks appears to have been motivated, at least in part, to assess the slope stability of the south flank.

“Giant Landslides of the Hawaiian Islands,” from Dr. Ken Hon’s Geology of the Hawaiian Islands GEOL 205: Lecture Notes. Great introduction to this topic, well-illustrated and very easy to read.

“The Great Crack Hike in Ka'ū,” hike description found on the tourism website Instant Hawaii, contains some great pictures of the crack. No doubt the acquisition of the crack by the NPS will change the hike description somewhat, however. See next reference.

John Burnett, “National Park Service acquires ‘Great Crack Property’ in foreclosure sale,” Hawaii Tribune-Herald, Friday, September 14, 2018, 12:05 a.m.

Field Trip Director

Annual Newsletter Editor

fieldtrips@gsoc.org